Blog

May Your Song Always Be Sung

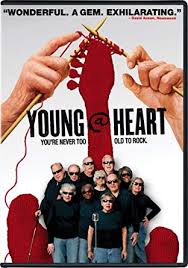

If you have never seen the documentary “Young@Heart” – please – stop what you are doing and immediately find this movie to view. The film was released about 10 years ago, and it is about a chorus in Massachusetts, the minimum age requirement being 70. Sure, you think, a chorus of seniors singing Mozart. Nope. Ok, well a chorus of seniors singing do-wop and the other music that comprised the songs of their youth in a fit of nostalgia. Nope, it isn’t that, either. They are singing a much more modern repertoire. In fact, their repertoire would make a chorus full of 40-year-olds balk, probably.

Director Bob Cilman founded the group in 1982, when he was a mere 29 years old, with the intention of having an elderly choir be dedicated to performing rock, punk, and soul music. Take a moment to let that sink in, then watch this awesome music video.

In the documentary about this group, Young@Heart singers are depicted performing songs like “Schizophrenia” by 80s alternative rock band Sonic Youth, “Should I Stay Or Should I Go?” by English punk bank The Clash, “Road to Nowhere” by new wave band Talking Heads, “I Wanna Be Sedated” by the post-punk band Ramones, “Forever Young” by folk artist Bob Dylan, “Fix You” by British rock band Coldplay, “Yes We Can Can” by New Orleans Jazz and R&B artist Allen Toussaint, and more.

You may have done the math as you were reading those titles: the fact that those songs are being sung by an elderly choir gives them a whole new meaning, or at the very least a bright new angle on the original meanings of each song.

Consider a 22-year-old who likes to party a little too much singing “I Wanna Be Sedated.” Now consider an 80-year-old singing it. The Young@Heart singers need do nothing to explain the change in meaning there. Likewise with the Bee Gees classic “Stayin’ Alive” – no explanation needed. Or, consider Bob Dylan’s song “Forever Young”

May your hands always be busy / May your feet always be swift / May you have a strong foundation / When the winds of changes shift / May your heart always be joyful / And may your song always be sung / May you stay forever young

These lyrics become especially poignant when sung by someone who may be closer in years to their own mortality than the then 32-year-old Bob Dylan who wrote it. The film shows the choir singing this to a group of inmates at a Hampshire County Jail. The movie shows that the group had just heard before this performance that one of the singing members had passed away; literally, they heard this news on the bus on the way to the prison to perform. They step out into that prison yard and just give it all of their hearts without being overly sentimental. They let the music do the talking. See that performance at the Hampshire County Jail here.

Some of the inmates are in tears over this pure expression of humanness. And you can’t help but wonder what it is like for the singers to be giving so much, receiving so much, and to be faced so squarely with their own mortality in the middle of performing this singular art form, one that offers nowhere to hide.

Aging is not for wimps, so they say.

Now the director is a youngster, in his early 50s when they filmed the documentary, and I’m happy to say is still at the helm of this group of musicians since he started the group in 1982. The documentary depicts him as a laid back guy, and he seems to take all the requisite challenges of this particular craft in stride.

Consider that he must also ride the emotional waves of his members dying. Frequently. While the choir members serve as emotional support for each other during those times of illness or death of the singers in the cohort, I can’t help but relate to the director. How hard must that be, to get so attached to folks, especially in the context of preparing and performing music together, only to have to let them go. Often. Directors of gay men’s choruses during the zenith of the AIDS crisis had to deal with the same repeated and frequent loss. Music fosters a uniquely salient attachment for many. Perhaps it is only music that can see people through that loss and transform it into an art that is almost universally accessible. Even those who did not directly experience the event or pain can have a moment of relating to the singer through music, which has the potential to heal.

I say music gives you nowhere to hide. If you give yourself to it fully, that is true. But when you are singing in a choir, in a group of somehow like-minded souls, it offers not a hiding place but rather sanctuary. Music is an art form that exists in time and is unlike any other art form in that way. It can be a singular expression, such as a solo voice with guitar, or a group expression, such as quartets, choirs, symphonies, and bands. Take a choir of many human voices and you have an even more unique expression. The human being expressing the art is also the instrument itself – there is no separation, no layer of remove such as when the first chair can put his violin down, or the jazz pianist can walk away from the piano she’s playing. When you are an instrumentalist connected to band mates and all is going well, it is a particular kind of exhilaration. And when you are a singer connected to others singing with you, it is soul work like no other.

Learn more about this amazing chorus at the Young@Heart Chorus website.

-Ellen Chase, Associate Artistic Director