Blog

Choir in the Time of COVID; Part I: The Day the Choirs Stood Still

Right now it is medically unsafe for groups of people to gather and sing. Choirs everywhere have been benched, full stop. And what is worse, the timeline is indefinite. For those of us who sing in choirs, for fun or for therapy or some mix of the two, this has been a catastrophic change.

I’ve come to think of this as “The Day The Choirs Stood Still”, borrowing a title from the iconic sci-fi movie from the 1950s. And, no, I’m not talking about choralography.

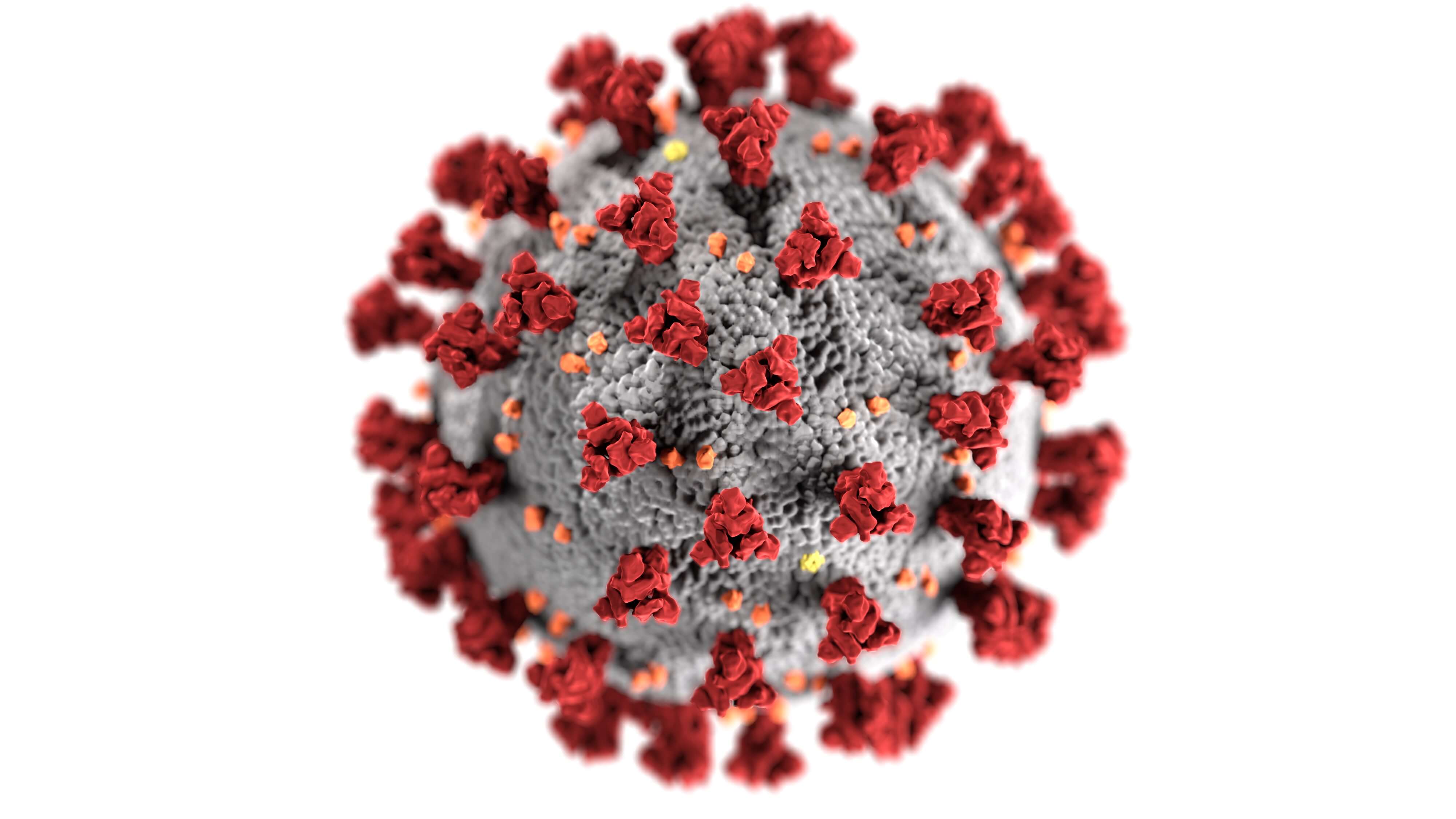

As I write this, the world is several months into a pandemic, a once-in-a-100-years type virus that has sickened millions and killed several hundred thousand. It has hit the United States particularly hard, for a variety of reasons we shan’t get into here. Scientists know some about the virus itself, but we do not know enough about the sicknesses caused by the virus, nor how to treat and cure them, because it is only a few months old. We don’t fully know how to prevent it from causing human sickness or death, though we have some ideas about transmission and (most of us) are dutifully trying to change our own habits to slow the spread of the virus. We do not know if or when life will return to “normal”; we do not even know what our new normal will be. Even for people who are not in high risk groups, society, and life as we know it has changed – possibly irrevocably – in many ways.

For musicians, this has been a bit of a strange time. I suppose if you are used to just practicing your instrument by yourself for hours a day, well, the early days of the pandemic would not feel too different. If you are the most incredible “couch” mandolinist, who loves to noodle and learn from instructional videos, and who never performs in a band, you probably have not had a vastly different musical experience during the shelter-in-place and gathering restrictions during this pandemic. But if you are a musician who is used to – and in fact, revels in – playing with others, why, this is a trying time, indeed.

Who knew that such a nerdy wholesome activity as

choral singing could become so dangerous? Before this novel coronavirus

pandemic, if you had ever asserted that being a choir geek could be – in any

way – life threatening, I would have questioned your sanity.

As anyone knows who has been in a choir with someone who had a common cold, respiratory illnesses can spread like wildfire through a singing group. When people are present in choir but are sick but don’t yet know it, or if singers are trying to push through their illness stoically (or heroically), or attempting to honor their commitments, or otherwise decide to sing in the choir at the moment they are contagious, there are devastating results. Whole choirs can spread a plain old cold virus like wildfire, wreaking havoc on, say, your Holiday concert when suddenly 80% of your singers lost their high notes. That has happened. I daresay anyone who has participated in choruses long enough has experienced or witnessed it, and it can be pretty bad. But this novel coronavirus is no common cold or even flu. Some who catch the virus do not get sick, or only get sick enough to see it as a bad cold; others have been hospitalized and some have to endure ventilators and the long-term effects of surviving that; still others perish. The long-term effects of having contracted it are totally unknown. It is such a moving target – and different countries have taken varying approaches to testing, containment, social distancing measures, and the like – that scientists can’t entirely agree on things like exactly how transmission happens and fatality rates.

Given we are still learning a lot about this novel virus – it is new to human beings and to the human scientists studying it – there is much we do not know about it and its spread. Yet we do know this is something even more highly contagious, and sometimes contagious well before people are symptomatic. We also know that is spread through either airborne or aerosolized respiratory droplets (along with contact with infected surfaces, face touching, etc.).

Well, guess what singing produces a lot of? Aerosolized and airborne respiratory droplets. Singing, done properly, uses even more air force than speaking, on average.

By now, many of you have seen Schlieren photography demonstrating fluid dynamics of respiration, speaking, and singing. Here are some more examples.

Speaking Schlieren image:

In a choral situation, or in a situation such as a religious service, it is many people singing simultaneously, so the amount of droplets emitted and breathed in would be orders of magnitude greater than, say, some people safely distanced apart at a grocery store or an outdoor restaurant.

Singing Schlieren image

Guess what else you do in singing? Breathe deeply. Often. And this novel virus targets the not only the upper human respiratory tract but also the lower, making it instantly more threatening than your average cold (aka upper respiratory infection). Unmasked singing, for the moment, is out. And masked singing is NOT risk-free, for droplets are reduced but still find their way into or out of certain mask designs and into the air. Singing with the face covered also poses problems for singers and directors alike, in the ways in which covering the main amplifier of human voice can distort sound. Interjection: Masks are effective and necessary, people. Just do it. Let’s get this: countries who have gotten the pandemic under control are strict about mask usage. I refuse to debate their validity in general. However, are masks a possibly for singing groups? That remains to be seen.

Imagine if you will, a group of 50 people standing shoulder to shoulder, sans masks, giving a nice loudly aspirated “T” at the end of a phrase, and then all breathing deeply to get ready for the next phrase. Now, imagine something nice like baby rabbits or blooming azaleas to get rid of the creepy image of breathing in other peoples’ “droplets” en masse. Eek! ::shudder:: In reality, though, choral musicians have always done this. Even with the danger of catching the occasional cold, choral singers get over the grossness of breathing in others’ miasma, because the payoff is worth it. Well, it was. Except that now, it may be deadly. Therefore, even the most hardcore choral nerd will admit, everything has to be reconsidered.

What will this mean for choirs in the short-term and long-term? Well it most certainly means it is unwise to gather together in person and sing, right now. Full stop. But for how long? No one knows that. And that is one of the things that makes this time period so difficult. Even as states start to reopen certain businesses and ease certain restrictions, choirs will remain shuttered, as a matter of life and death. Some directors and organizations have explored the idea of getting together to sing with various restrictions. We will go over the myriad of ideas on that [later], but suffice it to say, singing together is currently on the spectrum between problematic and possibly deadly.

Why does this matter? Some of you may be thinking “who cares, it is just choir, y’all seriously need to get over it. So you can’t meet for <insert vague amount of time here>. So what?!” I’m guessing the person who thinks this certainly hasn’t read this far into the article, but let us explore the point anyway. Life has shifted immeasurably over these last months. For many people, some of the hobbies that we counted on for stress-reduction and other benefits have been suspended. If you are in a darts or recreational softball league that can no longer meet due to social distancing guidelines, you are probably feeling it. Disappointed. Missing it. But your life may be so full of other things – at home hobbies you can explore, or figuring out this working from home reality, caring for children, or god-forbid both at the same – that perhaps you have a slight “bummer” feeling about missing darts at the local bar every Wednesday night, but you know you will be able to do that again later. Heck, you might even order your own board and keep practicing at home to keep your game fresh.

For some people, singing in an adult choir is just that, a hobby. They like to go, sing a little, go home. And perhaps for them, the absence of singing in a choir is not “felt” too strongly. But for most who sing in choirs, especially adults, there is a lot to gain out of the experience. When you were a child, or even college age, perhaps you sung in a choir in place of worship or school because you had to, or you needed that fine arts credit on your transcript. Yet, as adults, we have a tendancy to be more choosey about where we spend our time, and we no longer need the grade. So why do we bother to sing in choirs? So many reasons.

Some people enjoy the personal growth that comes from learning and performing challenging repertoire. Some enjoy being a part of a group that is singularly focused toward one goal. That can inspire a feeling of comraderie and social bonding between members of the group. Also, it can bring on feelings of co-creation, which is both satisfying for each participant and rewarding. Some believe that, just as physical exercise is necessary for body health, the cognitive challenges represented by technical aspects of singing, learning and memorizing new music are useful for brain health.

We all know that listening to music can elicit emotional responses, and scientists have also proven that hearing music can elicit chemical and hormonal responses unseen in the body. But scientists have also proven that the act of singing in a group elicits even greater chemical responses. One researcher who has studied music’s effects extensively is German professor Gunter Kreutz, who has authored and contributed to many studies on the subject. One exciting paper to which he contributed is titled “Effects of Choir Singing or Listening on Secretory Immunoglobulin A, Cortisol, and Emotional State” originally published in 2003 in the Journal of Behavioral Medicine. Words like “secretory” and “immunoglobulin” are not the only exciting things going on in in this study.

Participants of this study were members of a community choir, and in the study, choir members in turn listened to, and sung a piece music while their physiological responses were recorded. Among their findings: singing increases the body’s immune response, listening to music has benefits but does not elicit the same physiological effects as singing. In a typically science-y understatement, the study concludes there may be “a possible influence of musical behavior on well-being and health.” In my experience, this is more than possible.

In another Kreutz study from 2018 titled “Psychobiological Effects of Choral Singing on Affective State, Social Connectedness, and Stress: Influences of Singing Activity and Time Course”, their findings “suggest that both singing activity and duration of singing modulate psychological effects” such as decreasing stress. This study also found that individuals had a “perceived social connectedness evolving over larger time spans than 30 minutes”. We can all cite examples of why social connectedness is important for humans; we are all enduring this pandemic-imposed period of time in which our ability to feel connected socially may be taking a hit. For those of us who relied on regular chorus rehearsals to feel connected, to live without such opportunities to connect is a difficult time.

Music meets us in places where speaking, and even thinking, can’t touch. I know I have relied a lot on the sense of community that comes of being a part of a like-minded group of singers. When a major trauma occurs, such as with the senseless deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, some choristers count on being able to meet together to discuss, sing, and process the grief they feel over these horrific events. What can we do? How can we move forward to create a better society? How can we heal the hurt? Some choruses themselves were founded, and sit on a foundation of, expressing need for social justice. For such groups, the “personal is political”, and the mere act of participating in that specific singing community weaves one into the fabric of social justice movements. It makes sense that this would be a difficult time for such singers, when the world is rife with burning issues that touch the heart and need to be felt and processed. And what better way than music, together?

Lastly, when one aspect of your identity is “singer” or “choral musician” or however you would like to label it, consider that, in this moment, you have temporarily lost that piece of your identity. Is it gone forever? No; most likely not. But even just losing it temporarily can cause the singer to grieve. This study shows that “non-bereavement” loss of a “self-defining” role, as in the case of divorce, job loss, or a chorister without choir, can cause “prolonged grief, posttraumatic stress and major depression” similar to a bereavement loss. How intense the grief was in each subject studied tended to rely on how fresh the loss was and how central it was to the person’s identity. Take OurSong, who had rehearsed for months on a project which was due to culminate in a concert and recorded album in March. Well, that got postponed indefinitely, because of the pandemic. While the group has continued to meet virtually, participated in virtual concerts, recorded a virtual choir piece, and done other things to try to stay connected, the project they were working on has no completion date in sight. No culmination. That piece of identity is, for the time being, lost. Fresh loss. How central it is to each singer’s identity is for her/him/them to decide. And it may be temporary, but it is a loss that needs to be acknowledged all the same.

There are things about this COVID-19 inspired confinement that have benefitted us. It is excellent that we are adopting – or trying to enforce – safe practices as a society. More and more people now have a consciousness around wearing masks to protect others, washing hands frequently and correctly, staying isolated when sick. We can also start to look at the importance of indoor ventilation systems and update that technology to be more supportive of our biological needs for fresh and clean air. All these potential changes are beneficial to the greater good.

But what about when your beloved avocation, one that helped you retain your sanity and give you a means of self-expression, has been cut off completely by this new disease?

It is one thing to have to take a break from a chorus in which you love to sing. Even devoted choristers take breaks all the time for major life events, and then they come back to group singing as soon as possible. It is another thing entirely to have it taken from you, with no good news about when it might possibly return.

I do feel sure about one thing: once they resume, no one will take a regular, mundane, weekly choir rehearsal for granted. Ever again.

Stay tuned for further installments of this series “Choirs in the Time of COVID”. We will be exploring topics like virtual choirs, online rehearsals, practicing at home, and recommendations for choirs who want to return sooner than later. In the meantime, please, stay well.

Ellen Chase

Additional material:

There is a nice article about many therapeutic effects of singing on the singer here.

An initial study which includes Schlieren images of emissions of various instruments; there will be another such study forthcoming.

Here is a Panel on Future of Singing from May 2020 about COVID-19 and singing, from the National Association of Teachers of Singing and Performing Arts Medicine Association: